Report 1

Armenia-Azerbaijan Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

A report by Steven Kay QC, Dréa Becker & Joshua Kern | 20th July 2021 | Download report

Return Home

Return Home

Report 1

A report by Steven Kay QC, Dréa Becker & Joshua Kern | 20th July 2021 | Download report

Azerbaijan established itself as the first republic in the Muslim Orient between 1918 and 1920, when it was incorporated into the Soviet Union and became one of the USSR’s constituent republics. On 30 August 1991, Azerbaijan declared its independence within the borders of the Azerbaijan SSR, including the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO). The 1977 USSR Constitution, preceded by its 1924 and 1936 Constitutions, explicitly stated which republics held a right of secession and limited their number to the fifteen Soviet republics forming the Constitutional parts of the USSR. 1

The right to secession contained in the Soviet Constitution granted to the Union republics is essential to our understanding of the application of the general principle of uti possidetis juris to this matter. These references to the constitutional right of secession are important when determining the status of administrative units, and the scope of their rights and autonomy. This was expressly recognised in the Badinter Arbitration Commission Opinions for Yugoslavia. The provisions of the USSR Constitution which stipulated the ‘sovereign Union republics’ right of secession, as well provisions which prescribed their territorial integrity, provided the basis for the consensual application of the uti possidetis juris principle once the former administrative borders of Soviet republics crystallised into the international borders of newly independent States.2

In the late 1980s, the Soviet Socialist Republic of Armenia laid claim to the NKAO of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan. On 15 June 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Armenian SSR adopted a resolution approving a decision made by the Congress of Armenian Delegates of Nagorno-Karabakh regarding unification of the NKAO with the Armenian SSR.3 The USSR authorities declared the Armenian legislature’s decision to be null and void ab initio and giving rise to a serious breach of the USSR Constitution. Thus, the Armenian territorial claims and actions were contrary to Soviet constitutional law. Meanwhile, nationalist forces in power in the Republic of Armenia commenced an aggressive campaign to occupy Nagorno-Karabakh and carried out attacks and assaults on Azerbaijanis who were forcibly expelled from both Nagorno-Karabakh and their historic lands in Armenia.

The dissolution of the USSR saw an increase in armed attacks against populated areas within Azerbaijan both by Armenia itself, and by Armenian forces in Nagorno-Karabakh. Hostilities soon escalated into a full-scale armed conflict between the nascent states. In the course of this conflict, Armenia occupied a significant portion of Azerbaijan’s territory, including Nagorno-Karabakh, seven adjacent districts,4 and Azerbaijani exclaves surrounded by the territory of Armenia. The war resulted in the deaths and wounding of thousands, and the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis. The exodus was the biggest instance of forced displacement in Europe since the end of the Second World War.5

Armenia’s use of force against Azerbaijan and its occupation of Azerbaijani territories have been consistently condemned by the international community.6 In 1993, the United Nations Security Council adopted resolutions 822, 853, 874, and 884 which reaffirmed Azerbaijan’s territorial integrity, and demanded the immediate, complete and unconditional withdrawal of Armenian occupying forces. In 2015, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights (in the case of Chiragov and others v Armenia) held that the Republic of Armenia is exercising effective control over the ‘NKR’. The Chiragov Decision was reaffirmed by the Court in Sargsyan v Azerbaijan (2015), Zalyan, Sargsyan and Serobyan v. Armenia (2016), and Muradyan v Armenia (2016). The ECtHR attributed State responsibility to the Republic of Armenia as an occupying power. Under international humanitarian law, and as an occupier, Armenia is specifically prohibited from engaging in any activities aimed at altering the legal system and changing the physical, cultural and demographic character of the territory it occupies. This includes prohibitions against the deportation or transfer of civilians, infringements on public and private property, pillage, and the exploitation of the resources of occupied territory for its benefit.

Since 1992 the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) has engaged in efforts to achieve a peaceful settlement of the conflict under the aegis of its Minsk Group. Despite this ongoing process, the policy and practice of Armenia clearly demonstrated its intention to secure the annexation of Azerbaijani territories it captured through military force.

Between 31 January and 6 February 2005, the OSCE Minsk Group Fact Finding Mission visited the seven occupied regions of Azerbaijan around Nagorno-Karabakh to examine the question of Armenian settlements in these territories. In a subsequent letter to the OSCE Permanent Council, the Minsk Group Co-Chairs noted that the “prolonged continuation of [settlers in occupied territory] could lead to a fait accompli that would seriously complicate the peace process” and discouraged “any further settlement of the occupied territories of Azerbaijan.”7 Following a further field mission in October 2010, they urged that “any activities in the territories […] that would prejudice a final settlement or change the character of these areas” should be avoided.8

In July 2020, Armenia proclaimed the so-called ‘Tonoyan Doctrine’, a strategy to capture further territory of Azerbaijan in a bid to force the latter to accede to the occupation of Nagorno-Karabakh and its surrounding regions. This strategy was juxtaposed with continued attacks on Azerbaijan’s civilian population. President Ilham Aliyev addressed these issues and Azerbaijan’s concerns at the 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly,9 where he noted that legal action would be taken against those responsible. Armenian attacks – including those carried out by their proxies – continued after President Ilham Aliyev’s address. The military action initiated by Azerbaijan on 27 September 2020 was an adequate and proportionate response to these continued acts of aggression. Azerbaijan, for its part, invoked its inherent right to self-defence under Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations.10

In October 2020, whilst the war was still raging, I instructed Steven Kay QC of 9 Bedford Row Chambers (9BR) and his team to report on and assess acts committed by Armenian forces. We visited locations in several districts where Azerbaijani civilians had been targeted, and also visited areas of the district (rayon) of Fizuli recently liberated from Armenian occupation. I requested the world’s leading experts in international criminal law to see with their own eyes the crimes that have been committed against the Azerbaijani people, and to carry out an initial assessment of their illegality and criminality under international law. This Interim Report is the result of great efforts of Steven Kay QC, Dréa Becker and Joshua Kern, actively supported by the team from my firm, BM Morrison Partners, and the Azerbaijani Bar Association led by its Chairman Anar Baghirov. A special thanks to all commentators including Dr Farid Ahmadov of ADA University for their feedback and comments.

This Interim Report divides into three parts. The first part addresses rocket and missile attacks on Azerbaijan’s civilian populations and infrastructure during the armed conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in September – November 2020, and the devastation witnessed by the 9BR team on the ground. The second part addresses the utter destruction caused during the Armenian occupation of the district of Fizuli, one of the seven occupied districts surrounding the Nagorno-Karabakh region, which was also witnessed by the 9BR team on the ground. The third part considers accountability mechanisms under applicable international conventions.

Part I: Attacks on civilians during 2020

Between 27 September 2020 and 10 November 2020, Armenian attacks on Azerbaijan’s cities, villages and settlements resulted in the death and wounding of civilians, as well as extensive damage to civilian property and infrastructure. These attacks may be characterised as war crimes incurring individual criminal responsibility under international law.

Attacks by Armenian forces killed 100 Azerbaijani civilians and injured 416 others.

Civilian casualties occurred on a near daily basis from the outbreak of hostilities on 27 September 2020 until the parties signed a Russian-brokered agreement on 10 November 2020.

Almost half of the civilian fatalities occurred in ‘single-fatality’ incidents.

There were dozens of attacks on villages, settlements and cities which did not result in civilian fatalities, but left civilians wounded, and civilian property and infrastructure destroyed or damaged.

Key Incidents: 27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020

This report considers in detail five attacks (‘key incidents’) by Armenian forces which all resulted in multiple civilian casualties:

Attack on Gashalti – 27 September 2020: In the first hours of the conflict, on 27 September 2020, Armenian forces launched an artillery attack which killed five members of the Gurbanov family in Gashalti village, Goranboy district.

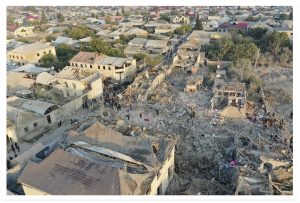

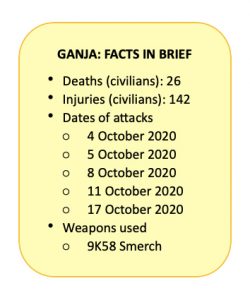

Attack on Ganja – 11 October 2020: On 11 October 2020, 10 civilians were killed and 39 civilians were injured in a Scud-b missile strike attack on a residential area of the city of Ganja.

Attack on Ganja – 17 October 2020: On 17 October 2020, 15 civilians, including six children, were killed and 60 civilians were injured in a Scud-b missile strike on a residential area of Ganja.

Attack on Barda – 27 October 2020: On 27 October 2020, five civilians, including a seven-year-old girl, were killed and 12 civilians injured in a cluster munitions attack on Garayusifli, a farming village in the district of Barda.

Attack on Barda – 28 October 2020: On 28 October 2020, 21 civilians were killed and over 90 were injured in a cluster munitions attack on a busy commercial and residential area of the city of Barda.

In total, 56 civilians were killed and over 200 civilians were injured in these five attacks. These attacks also resulted in extensive damage to civilian property and infrastructure.

9BR visits

In November 2020, the 9BR team visited incident locations in the Azerbaijani districts of Barda, Terter, Ganja and Goranboy. We witnessed the aftermath of missile strikes in civilian areas and saw the scale and nature of destruction to civilian property. We spoke to survivors and family members of those killed in the attacks.

The 9BR team visited Gashalti and saw the destruction to the Gurbanov home. We spoke to Nadir Gurbanov, the surviving widower, and villagers who tried to assist in the aftermath of the attack. Witnesses told us that at the time of the attack, the Gurbanov family were gathered at the entrance of their home, watching the hostilities taking place far in the distance.

In Ganja, we observed a large crater left by the missile warhead in the attack on 11 October 2020, and the vast area of destruction from the attack on 17 October 2020. These were densely populated residential areas, now in ruins. Clothes, shoes and other personal possessions were strewn within the rubble. Vehicles were crushed, warped and destroyed. Whilst the foundations or partially collapsed walls of some homes were still visible, others were completely reduced to twisted metal, stones and shards of wood.

In Barda, we visited the site of the 28 October 2020 attack. It was clear that the area was civilian in nature, with a mix of commercial and residential properties. The impact damage from the weapons deployed was still visible on the street intersection, as was the widespread damage to homes and small businesses. We observed destruction consistent with cluster bomblets and fragments, dispersed over a large area.

Attacking civilians

Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited. Indiscriminate attacks are those which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; attacks which employ a method or means of combat which cannot be directed at a specific military objective; or attacks which employ a method or means of combat the effects of which cannot be limited.

Armenian forces fired highly destructive and inaccurate weapons into villages and towns in Azerbaijan. We have concerns that the Grad missile fired into the Gurbanov home in Gashalti on the first day of hostilities was not accurately directed at a specific military objective.

Scud-B ballistic missiles fired into densely populated residential areas of Ganja city are inaccurate and can land hundreds of metres from any intended military target. Missiles armed with cluster munitions, such as those fired on Garayusifli village and Barda city are not only inaccurate as to the missile’s specific target, but also spread bomblets and fragments over a wide area. Unexploded bomblets can result in long-term effects on a civilian population.

Armenian forces carried out attacks which resulted in the death or serious injury to civilians in the villages of Gashalti and Garayusifli village, and the cities of Ganja and Barda. Indiscriminate weapons were used in civilian areas.

Making civilians the object of attack is a grave breach of Additional Protocol I when committed wilfully. Indiscriminate attacks may qualify as direct attacks against civilians: intent may be inferred from the specific nature of the attack, including the nature of the weapons used. In some circumstances, that an attack is directed against civilians may be obvious because of the type of weapon used.

Armenian forces attacked on Ganja city on 11 October and 17 October 2020, and Barda city on 28 October 2020. These attacks deployed inaccurate weapons, such as Scud-b missiles and cluster munitions, directed towards densely populated cities indiscriminately. There are grounds to infer that these attacks must have been carried out in the knowledge that civilians were being targeted.

As such, there are reasonable grounds to allege that Armenian forces committed grave breaches of Additional Protocol I by targeting civilians during the armed conflict of 2020, and that those responsible are liable to criminal prosecution pursuant to States Parties’ obligation to repress grave breaches.

Disproportionate attacks

Indiscriminate attacks are those which strike military objectives and civilians (and civilian objects) without distinction. Based on the available evidence, there are grounds to conclude that Armenian forces carried out indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks during the armed conflict of 2020, treating as a single, military, objective cities where military objectives may have been located, or (in the case of Gashalti village and Shikharkh settlement in Terter), civilian areas which may have been adjacent to where Azerbaijani forces were stationed.

Accordingly, there are reasonable grounds to allege that Armenian forces committed grave breaches of Additional Protocol I by carrying out indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks during the armed conflict of 2020, and that those responsible are liable to criminal prosecution pursuant to States Parties’ obligation to repress grave breaches.

Crime against humanity – murder / grave breach of wilful killing

There are grounds to support an allegation that Armenian attacks on Ganja city on 11 October and 17 October 2020 were directed against the civilian population. Indiscriminate Scud-B ballistic missiles were fired on a densely populated city where there was no clear military objective in the vicinity. The circumstances of these two attacks may further demonstrate that the intent of those launching the attacks was to kill civilians.

To be characterised as a crime against humanity, a murder must have been committed as part of widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population. To be characterised as a war crime, the victim must be a protected person. Further investigation is required to ascertain whether these key incidents may have been part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against the civilian population of Azerbaijan. However, it is clear that victims were protected persons.

The number and nature of these attacks may indicate that Armenian forces pursued a policy of targeting Azerbaijan civilians. We note admissions by Armenian authorities (and de facto authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh). Vagram Pogosian, a spokesperson, posted the following on Facebook on 5 October 2020: “a few more days and I’m afraid that even archaeologists will not be able to find the place of Ganja. Get sober, before it is too late.” The following day, Vagharshak Harutyunyan, chief advisor to the Prime Minister of Armenia, said on Russian television that Armenian forces were deliberately targeting the civilian population of Azerbaijan.

Part II: Occupation of Fizuli

Background

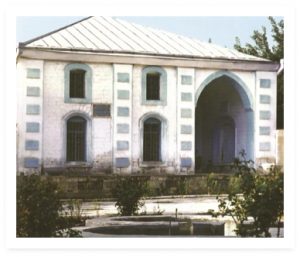

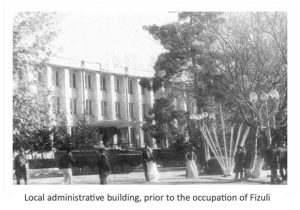

The rayon of Fizuli (Füzuli rayonu) is an administrative region of the Republic of Azerbaijan in the south-eastern part of the country. It neighbours the Islamic Republic of Iran and has an area of 1,386 km2. The district has a rich historical past and diverse cultural legacy and was home to ancient residential areas, tombs, caravanserai, and mosques.

Prior to the Armenian occupation, the district contained one town, one settlement, and 75 villages. It is reported there were 86 secondary schools, two vocational schools, 54 kindergartens, 10 music schools, 27 clubs, two museums, 90 libraries, 13 hospitals, 17 medical treatment points, and 48 maternity services centres there.

Approximately one third of the district, including the town of Fizuli, was occupied by Armenian forces on or around 23 August 1993. Azerbaijani forces recaptured Fizuli on 17 October 2020.

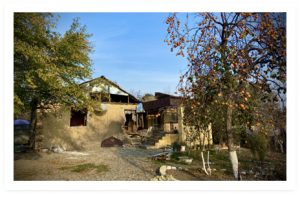

9BR visit to Fizuli

The 9BR team visited the Fizuli district on 21 November 2020. Approaching from the south, the team was joined by Deputy Chief of Police Ralph Abdul Karimov.

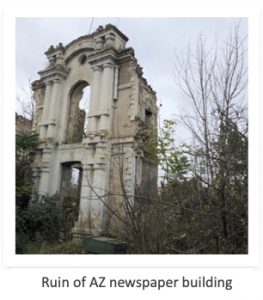

Extensive destruction was immediately visible upon crossing the former line of contact. The ruins of destroyed buildings and physical infrastructure lay all around. Not a single building visibly appeared to have been left standing.

The 9BR team saw large quantities of piping collected and deposited on the side of the road. Abandoned bulldozers appeared among the ruins. Physical infrastructure appeared to have been appropriated.

In the ruins of the village of Dadali, isolated standing gravestones indicated a destroyed cemetery.

Fizuli’s mosques, museums, hospitals, schools, monuments, theatres, libraries and cultural centres are all destroyed. The town and formerly occupied villages of the district are all utterly destroyed.

In the town of Fizuli, there was only shrubland and ruins. In the cemetery, gravestones have been overturned and smashed.

Extensive destruction

The scale of the destruction caused to the Fizuli district comfortably falls within the definition of “extensive” destruction for the purposes of qualifying the conduct as a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions.

The scale of devastation appears difficult to justify on grounds of military necessity.

We have grounds to allege that the grave breach of extensive destruction of property was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation. There are also grounds to believe that the conduct of Armenian forces may also be punished as prohibited destruction.

Extensive appropriation

International Crisis Group reported in 2012 that “whole towns” had been “systematically dismantled by Armenian forces” and carried away for scrap.

This finding appeared to be corroborated by the sight on the ground where piping deposited on the side of the road in Ishygly village suggested that the destruction of infrastructure was caused with the intent to appropriate it.

We have grounds to allege that the grave breach of extensive appropriation of property and the war crime of pillage were committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation.

Destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science

The wholesale destruction of Fizuli’s mosques and religious buildings, its educational institutions, and its hospitals may be punished as the war crime of destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science.

Crimes against humanity: persecution

There are grounds to allege that the destruction of Fizuli, carried out in connection with an armed conflict which entailed the looting and burning of Azerbaijan’s towns and villages, and massed forced displacement, can be characterised as being connected to a widespread and systematic attack directed against the civilian population in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan.

We also have grounds to allege that the destruction in Fizuli was carried out with a specific intent to discriminate on ethnic and national grounds, and may arguably be characterised as the crime against humanity of persecution.

Part III: Accountability

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 and (in Armenia’s case) Additional Protocol I of 1977 create obligations on States to extradite or prosecute individuals responsible for violations which also constitute grave breaches.

It is these instruments which currently engender the most fruitful potential for criminal law enforcement over the crimes analysed in this Interim Report.

The republics of Armenia and Azerbaijan have been locked in a bitter dispute over the territory known as Nagorno-Karabakh since before the collapse of the Soviet Union. As noted in Dr Mirzayev’s preface, the territory is internationally recognised as part of Azerbaijan. The ethnic Armenian community of Nagorno-Karabakh’s efforts to secede from Azerbaijan 1988 and Armenia’s claims to this territory was the catalyst for a bloody war, which ended with the Russia brokered ceasefire in May 1994, and was punctuated by the ethnic cleansing of Azerbaijanis from Azerbaijani sovereign territory occupied by Armenian forces. As a result of the war, over 300,000 Azerbaijani refugees left Armenia and about seven hundred thousand Azerbaijani civilians were displaced. Approximately 30,000 people were killed. Since then, up until 10 November 2020, Armenian forces were in effective control as occupier of both Nagorno-Karabakh and seven adjacent districts of Azerbaijani territory.11

Azerbaijan asserts that the 2020 conflict arose from the implementation of unlawful Armenian policies and notes that the hostilities took place exclusively on Azerbaijan’s sovereign soil.12 The deployment of a large number of Armenian troops and armaments in Azerbaijan’s sovereign territory, Azerbaijan argues, establishes that Armenia was the aggressor and was pursuing annexationist objectives.13 Azerbaijan alleges that Armenia had been unlawfully seeking to consolidate its occupation of the Nagorno-Karabakh region and the surrounding seven districts, to change their demographic composition, to prevent the return to their homes and properties of hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijani internally displaced persons, and to exploit and pillage their natural resources and other wealth.14 Together with ongoing destruction and appropriation of property, and the targeting of civilians and civilian objects, Azerbaijan alleges that Armenia was responsible for the committing of war crimes both prior to and during the 2020 armed conflict.

Armenia, for its part, asserts a claim of self-determination on behalf of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh and argues that by “virtue of this right, the people of Nagorno-Karabakh should be able to determine their status without limitation.”15 Although Armenia asserts no express sovereign claim of its own to the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, it acts as the agent / delegate of the territory’s de facto authorities before the organs of the United Nations, a practice which has been rebuked by Azerbaijan, but which also demonstrates the absence of foreign relations capacity of the de facto Nagorno-Karabakh authorities, an constitutive element of objective statehood under the Montevideo Convention criteria.16

Hopes for fresh Armenian approach emerged with the election and ascent to power of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan in May 2018. As a (so-called) former ‘human rights defender’, Mr Pashinyan was elected on a tide of fresh expectations. However, by 24 September 2020, Azerbaijan was asserting that, since assuming power, the new Armenian government had replicated the annexationist policy of its predecessors and had adopted a military doctrine and national security strategy which envisaged a “new war for new territories.”17

Azerbaijan argues that the conflict of 2020 was initiated when Armenia attacked the Tovuz area of Azerbaijan between 12 and 16 July. The attack was not spontaneous, argues Azerbaijan, but “a clear manifestation of Armenia’s illegal use of force against the Republic of Azerbaijan”18 in pursuit of a goal to seize “a new part of Azerbaijan.” After the July attack, Armenia is said to have concentrated its forces along the line of contact between the parties’ forces. Armenia’s threats to strike Azerbaijan’s civilian infrastructure and residential areas were accompanied by intensified military reconnaissance deep inside Azerbaijani territory.19 In parallel, “Armenia announced the establishment of a civilian militia consisting of tens of thousands of civilians who would be forced to undertake military actions against Azerbaijan.”20

The conflict intensified on 27 September 2020 with the start of large-scale operations and, notwithstanding ceasefires announced on 10 October and 17 October, continued with increasing ferocity until the announcement of a Russian negotiated armistice agreement on 10 November 2020. In that time, Azerbaijani cities had come under rocket and artillery fire causing a high number of civilian casualties.

Prior to November 2020, diplomatic efforts to resolve the conflict were spearheaded by the OSCE’s Minsk Group. During the conflict, the Minsk Group’s co-chairs issued several statements calling for an immediate cessation of hostilities and resumption of dialogue.21 However, the eventual peace agreement between the parties was brokered by Russia.

Methodology and Conclusions

This Interim Report is funded by Dr Farhad Mirzayev of BM Morrison Partners, and is independent of the government of the Republic of Azerbaijan. It follows a visit to the Republic of Azerbaijan made by a 9 Bedford Row team comprised of Steven Kay QC, Dréa Becker, and Joshua Kern in November 2020. The team’s visit was made in the immediate aftermath of six weeks of active and intense hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan between 27 September and 10 November 2020. The visit was organised and actively supported by the team of BM Morrison Partners law firm and the Azerbaijani Bar Association.

The 9BR team carried out on site visits to incident locations in the districts of Barda, Terter, Ganja and Goranboy. We witnessed first-hand the aftermath of missile attacks in civilian areas. We visited the formerly occupied territory of Fizuli district and witnessed the utter devastation wrought during the period of Armenian occupation.

Our observations in situ were supplemented by meetings with survivors and representatives of official bodies, non-governmental organisations, and specialist agencies. We reviewed reports on the incidents which included the types of weaponry recovered and the nature of the destruction, deaths, and injuries.

Based on these observations and reports, and the analysis of the applicable international criminal law, this report concludes that during the recent conflict, there are grounds to allege that the armed forces of Armenia forces carried out indiscriminate attacks on cities and villages in Azerbaijan, that these unlawful attacks resulted in civilian fatalities and injuries, and that they caused widespread destruction and damage to civilian property and infrastructure. Specifically, we conclude that:

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the grave breach of attacking civilians was committed by the armed forces of Armenia during the relevant period (27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020).

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the grave breach of causing excessive incidental death, injury or damage was committed by the armed forces of Armenia during the relevant period (27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020).

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the grave breach of wilful killing was committed by the armed forces of Armenia during the relevant period (27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020); and

there are reasonable grounds to allege that murder as a crime against humanity was committed by the armed forces of Armenia during the relevant period (27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020).

Moreover, we conclude that during the period of the Armenian occupation of Fizuli (and reportedly in other occupied regions), Armenian forces carried out extensive and widespread destruction and appropriation of civilian property, including hospitals, schools, and cultural property. Specifically, we conclude that:

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the grave breach of extensive destruction and appropriation of property was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation between 1993 and 2020;

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the war crime of prohibited destruction was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation between 1993 and 2020;

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the war crime of seizure, destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation between 1993 and 2020;

there are reasonable grounds to allege that the war crime of pillage was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation between 1993 and 2020;

there are reasonable grounds to allege that persecution as a crime against humanity was committed in the Fizuli district during the period of Armenian occupation between 1993 and 2020.

It is important to note that these offences are international crimes incurring individual criminal responsibility under international law. As this Interim Report shows, the Republic of Azerbaijan has grounds to undertake legal steps against those responsible including through reliance on the accountability mechanisms which operate under applicable international Conventions. The Interim Report details the grounds that States possess to prosecute or extradite relevant persons when exercising jurisdiction pursuant to applicable international Conventions, including the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and its First Additional Protocol of 1977.

We are aware of reports that the destruction wrought in Fizuli during the Armenian occupation has also occurred in other formerly occupied districts of Azerbaijan. By destroying Azerbaijani cultural and religious establishments, cultural heritage and property in Fizuli and in other occupied territories, Armenia is arguably also in breach of its obligations to prohibit and eliminate discrimination, and to protect the enjoyment of rights by Azerbaijanis pursuant to Articles 2 and 5 of the 1969 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD). Both Armenia (1993) and Azerbaijan (1996) have ratified the ICERD and accepted the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) with respect to any dispute arising from the Convention which is not settled by negotiation or by the procedures provided for in it. Further investigation is required to ascertain whether any grounds for a claim made by Azerbaijan against Armenia pursuant to the ICERD can be sustained.

In this Interim Report, we review and assess incidents in the September to November 2020 armed conflict between the Republic of Armenia and Republic of Azerbaijan and consider whether offences may have been committed under customary international law and applicable Conventions. This review is with exception to the crime of aggression, and the assessment of the jus ad bellum is outside the scope of this Interim Report.

We have also addressed offences which it has been suggested have been committed in the part of the district of Fizuli that was occupied by the Republic of Armenia between 23 August 1993 and 17 October 2020.

Not all violations of international humanitarian law necessarily constitute war crimes. It is only violations of international humanitarian law which have been ‘criminalised’ (i.e. with respect to which customary or treaty law establishes individual criminal responsibility) that qualify as war crimes.22 In an international criminal law analysis, principles of international humanitarian law nevertheless remain essential to assessments of the legality of attacks as well as a belligerent’s conduct in situations of occupation.23

International humanitarian law prohibits the targeting of any non-combatant with armed force or any object that does not qualify as a military objective, namely an object which by its nature, location, purpose or use, makes an effective contribution to the military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture, or neutralisation, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage.24 Core principles include the principle of distinction (between legitimate and prohibited targets), and the obligation of all parties to conflict to take all feasible precautions to spare civilians and civilian objects.25 The principle of proportionality requires that “parties to the conflict must refrain from attacks against military objectives that may be anticipated to cause civilian casualties, or damages that are disproportionate in relation to the intended military goal.” This includes a prohibition of causing excessive incidental damage or casualties by targeting military objectives.26

Existence of an armed conflict

The connection between an offence and an armed conflict is what distinguishes a war crime from an offence under ordinary criminal law. The Tadić Appeals Chamber defined an armed conflict as existing “whenever there is a resort to force between States or protracted armed violence between governmental authorities and organized armed groups or between such groups within a State.”27 Common Article 2 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 provides that all four Geneva Conventions apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties. The Conventions also apply to all cases of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party, even if the occupation meets with no armed resistance.28

In Part I of this Interim Report, we assume that there was an armed conflict between Azerbaijani and Armenian forces between 27 September 2020 and 10 November 2020. This is not to say that an armed conflict did not subsist outside of these dates too. However, this assumption grounds the analysis which follows as it establishes the nexus between the acts which are analysed and an armed conflict for the purpose of their classification as war crimes.

In Part II of this Interim Report, for the reasons which are provided,29 we assume that approximately one third of the district (rayon) of Fizuli was under the occupation of Armenian forces between 23 August 1993 and 17 October 2020.

International armed conflict

An international armed conflict has been said to exist where a “state uses armed force against another state or its territory, be it through its armed forces or other, including private actors.”30 The unauthorised presence of foreign troops on another state’s territory may be an indication of an international armed conflict.31 As noted, international humanitarian law also applies to situations of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party to the Geneva Conventions, even if the occupation meets with no resistance.32

An internal armed conflict may become international if some of the participants in an internal armed conflict act on behalf of another State. The Tadić Appeals Chamber held that three distinct criteria could be applied, depending on the nature of the entity in question, to establish that participants in an internal conflict had acted on behalf of another State and thereby lending an international character to the conflict. These are the criteria of:

overall control (for armed groups acting on behalf of another State);

specific instructions or public approval (for individuals acting alone or militarily unorganised groups);assimilation of individuals to State organs on account of their actual behaviour within the structure of the State.

33

In 2015, the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights considered, in the case of Chiragov and others v Armenia,34 whether the Republic of Armenia exercised and continued to exercise effective control over the territory of the NKAO and the surrounding territories (including Fizuli) [H9]. The assessment depended primarily on military involvement but other indicators, such as economic and political support, could also be relevant. The Grand Chamber found that the Republic of Armenia, through its military presence and provision of military equipment and expertise, had been significantly involved in the conflict from an early date and that Armenian and the de facto authorities’ armed forces were highly integrated. The de facto authorities were also politically and financially dependent on Armenia [169]-[186].

Given the strength of the authority of the Grand Chamber’s Decision, deriving from the meticulous manner in which the specific question before the Chamber was addressed, for the purpose of this Interim Report we have assumed as correct the conclusion that the Republic of Armenia exercised effective control over Nagorno-Karabakh and the seven surrounding districts of Azerbaijan between the conclusion of the ceasefire between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 1994, and its associated hostilities, and the recapture of territory by Azerbaijan during the armed conflict of 2020.

Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 provide for individual criminal responsibility of persons committing grave breaches.35 The list of grave breaches is contained in each of the four Conventions. The scope of the Conventions’ application is indicated in Common Article 2 as limited to situations of an international armed conflict; accordingly, the concept of grave breaches is limited to international armed conflicts.36 We have seen, however, that Conventions also apply to circumstances of occupation as defined by Common Article 2.37

In general, the Geneva Conventions are concerned with the protection of civilians and non-combatants who are under the control of the party to the conflict. The Conventions, by and large, do not regulate methods and means of warfare.38 They do however include the grave breach of extensive destruction and appropriation of property, which we assess below in light of Armenian conduct in occupied Fizuli between 1993 and 2020.39 They also include the grave breach of wilful killing, which we assess below.

Grave breaches of Additional Protocol I

The list of grave breaches of Additional Protocol I is contained in Article 85.40 Additional Protocol I applies to international armed conflicts.41 Criminal offences include the grave breach of intentionally directing attacks against civilians not taking direct part in hostilities, and the grave breach of causing excessive incidental death, injury, or damage. We assess these crimes below in light of Armenian conduct during the armed conflict of 2020.42

Serious violations of the Laws and Customs of War

Serious violations of laws and the customs of war are war crimes under customary international law that are not proscribed as grave breaches. There are two immediate prerequisites under customary international law: there must be an armed conflict, whether international or internal in character,43 and there must be a nexus between the crimes alleged and the armed conflict.44 The Accused must know or have reason to know the factual circumstances demonstrating that there was an armed conflict.45 Crimes include the destruction or wilful damage done to institutions dedicated to religion, charity and education, the arts and sciences, historic monuments and works of art and science, the war crime of prohibited destruction, and the war crime of pillage. We assess these crimes below in light of Armenian conduct in occupied Fizuli between 1993 and 2020.46

The ICTY Appeals Chamber in Tadić set out the conditions that must be fulfilled for a violation of international humanitarian law to be made subject to ICTY jurisdiction as a serious violation of the laws and customs of war:47

the violation must constitute an infringement of a rule of international humanitarian law;

the rule must be customary in nature or, if it belongs to treaty law, the required conditions must be met;48

the violation must be “serious”, that is to say, it must constitute a breach of a rule protecting important values, and the breach must involve grave consequences for the victim. Thus, for instance, the fact of a combatant simply appropriating a loaf of bread in an occupied village would not amount to a “serious violation of international humanitarian law” although it may be regarded as falling foul of the basic principle laid down in Article 46(1) of the Hague Regulations (and the corresponding rule of customary international law) whereby “private property must be respected” by any army occupying an enemy territory;

the violation of the rule must entail, under customary or conventional law, the individual criminal responsibility of the person breaching the rule.49

Crimes against humanity

Crimes against humanity has existed as a category of crimes under international criminal law, arguably since before Nuremberg.50 Each of the international and (so-called) ‘hybrid’ tribunals have had jurisdiction over crimes against humanity. However, the scope and definition of both the chapeau elements of crimes against humanity, as well as of the underlying offences themselves, has not been consistent in practice. Discerning the precise scope and definition of the offence under customary international law remains subject to debate. It is with these qualifications in mind that the elements and definition of crimes against humanity are assessed in this Interim Report.

In this report, we assess the crime against humanity of persecution in the context of Armenian conduct in occupied Fizuli between 1993 and 2020.51 We further assess the crime against humanity of murder in the context of the conduct of Armenian forces during the armed conflict in 2020.52

Serious violations of the Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention

Article 15 of the Second Protocol to the 1954 Hague Convention establishes, as serious violations of the Protocol, certain criminal offences which might be committed against cultural property. Article 15 recognises that a person may be held criminally liable for serious violations of the Convention if they, intentionally and in violation of the Convention or Second Protocol, commit offences including “extensive destruction or appropriation of cultural property protected under the Convention and this Protocol” and “theft, pillage or misappropriation of, or acts of vandalism directed against cultural property protected under the Convention.” We assess these crimes in the context of Armenian conduct in occupied Fizuli between 1993 and 2020.

ATTACK ON GASHALTI VILLAGE

In the first hours of hostilities on 27 September 2020, Armenian forces launched an attack on Gashalti village. Five members of the Gurbanov family, including two children, were killed when a Grad missile struck their home.

Just over one thousand people live in Gashalti village, which is located on the outskirts of the city of Naftalan in the district of Goranboy.

Nadir Gurbanov, a military serviceman, was stationed approximately three kilometres away when he saw shells landing in the area of his village. He rushed home and discovered that the attack had killed his parents Elbrus and Shafayat, his wife Afag, his 13-year-old son Shahriyar, and his 14-year-old niece Fidan.53 Nadir’s cousin Mohammad said that in the aftermath of the attack, he found his cousin Nadir at the house, hugging pieces of children’s bodies. They were charred beyond recognition.54

Following the attack, Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) determined a Grad 9M22u, which is large calibre artillery, had been fired at the Gurbanov home.

The 9BR team visited Gashalti and saw the destruction to the Gurbanov home. The structure was badly damaged. Blood stains covered both the exterior and interior walls of the home.55

We spoke to Nadir Gurbanov and villagers who tried to assist in the aftermath of the attack. Witnesses told us that at the time of the attack, the Gurbanov family were gathered at the entrance of their home, watching the hostilities taking place far in the distance. The village overlooks a large area of fields and hills. Villagers pointed the area in the distance where they said military activity was taking place.

Witnesses confirmed that there was no military activity in the village, and that the nearest military position was that of Nadir Gurbanov’s regiment, kilometres away. Satellite imagery obtained by Human Rights Watch indicates that Azerbaijani forces may have been deployed in a large area extending from the southern boundary of the village to the eastern side of the road leading to the village of Tapqaraqoyunlu.56

ATTACKS ON GANJA

In the early hours of 11 October 2020, 16-year-old Sevil Aliyeva was at home with her parents and younger brother Huseyin. After almost two weeks since fighting had resumed over Nagorno-Karabakh, a humanitarian ceasefire had just been agreed between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Sevil was watching a movie as her parents slept. At approximately 2am she heard a “huge crash”. Sevil later described how large pieces of stone fell on her, as the walls of their home collapsed. Her parents, Anar Aliyev and Nurchin Aliyeva, both in their 30s, were killed. Sevil and her brother Huseyin, 8, are now orphans.57

The Armenian attack which killed Sevil’s parents was one of the deadliest, but it was not the first nor was it to be the last to claim the lives of civilians in Azerbaijan’s second city of Ganja.58 Ganja is located approximately 241km from the Armenian border, and 97km from what was the ‘line of contact’.59

Between 27 September to 10 November 2020, attacks on Ganja resulted in the deaths of 26 civilians and the wounding of 142 civilians, as well as extensive damage to civilian property.60 Azerbaijan asserts that in its attacks on the district Armenian forces were deliberately targeting civilians and civilian objects, in violation of international humanitarian law.61

In the early hours of 4 October 2020, Armenian forces launched “massive missile attacks” against Azerbaijan, with residential areas of Ganja city sustaining strikes from multiple rocket launch systems.62 According to Azerbaijan’s Ministry of Defence, the city was hit with tactical missiles using Smerch, Uragan and Grad rocket launch systems. Missiles hit various residential areas within the city, including the densely-populated neighbourhood of Gulustan.63 One civilian – 21-year-old Tunar Qoshqar Aliyev – was killed and 32 others, including six children, were injured.64

Attacks: 27 September – 10 November 2020

Civilian casualties were in addition to serious damage to the city’s civilian infrastructure, property, and historical buildings.65 29 residential apartments were destroyed and 118 were damaged.66 Residents told journalists of their fear and shock upon hearing a large explosion and the chaos that ensued. A nurse told the BBC that several civilians were seeking treatment in the hospitals, and that “there are casualties all over the city.”67 Azerbaijan accused Armenia of targeting its cities and in so doing critical civilian infrastructure of regional importance, all of which is situated far away from the conflict zone.68

The day after this first fatal rocket attack on the city, Vagram Pogosian, spokesperson for the self-proclaimed authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, posted a warning on social media: “A few more days and I’m afraid that even archaeologists will not be able to find the place of Ganja. Get sober, before it is too late.”69

The attacks on Ganja continued. Armenian forces launched further missile attacks the following day on 5 October 2020. Three civilians were injured when Smerch missiles hit Nizami Avenue and damage was reported in several areas of the city. Three apartments, a market and a secondary school were damaged in the attack. Additional shells landed in residential and commercial areas but failed to explode.70 Smerch missiles hit the Janpolad café on Hasan Aliyev Street on 8 October 2020, damaging the adjacent prison facility and resulting in injuries to three detainees. A school and a cinema were also damaged in the attack.71

The destruction wrought in the early hours of 11 October 2020 was widespread. The residential area of the city adjacent to Victory Park was hit by a 9K72 Elbrus ‘Scud’ tactical ballistic missile72 resulting in the collapse of several multi-storey apartment buildings.73 Azerbaijan asserts that this attack – just hours after the establishment of a humanitarian ceasefire – was launched from the Armenian city of Vardenis.74

When the 9BR team visited the site of the strike, we observed a large crater left by the missile warhead. Clothes, shoes, and other personal possessions were strewn within the rubble. Vehicles were crushed, warped and destroyed. Whilst the foundations or partially collapsed walls of some homes were still visible, others were completely reduced to twisted metal, stones, and shards of wood.

We were told that in the aftermath of the attack, people were searching by hand through the rubble to find survivors.

The area was not only clearly a civilian one, but a densely populated residential area near the centre of the city. The Scud missile landed on homes on Alakbar Rafibeyli Street, located behind a row of small shops and businesses. The damage extended far beyond the immediate vicinity of where the missile landed. The foundations of buildings even some distance away had collapsed, and there was damage to dozens of other homes and businesses. A Russian Orthodox church, built in 1887, was described as “heavily damaged” by the shelling.75 Nine multi-storey apartment buildings and 82 private houses were destroyed or damaged in the attack.76 In addition to damage to commercial businesses, a music school and kindergarten were damaged.77 An area of approximately 80,000 m2 within the city was affected by the missile attack.78

The strike killed ten civilians – including the parents of Sevil and Huseyin – as well as three members of the Alasgarov family: Ulvi, 30, Tarana, 55, and Durra, 53, who were killed with the missile hit their home. Gunay Aliyeva, who was pregnant, initially survived the blast but later died in hospital. She was 28 years old. Her husband Adil, also 28, and his mother Afag, 63, were also killed. Gunay and Adil were survived by their two-year-old daughter Nilay.79

39 civilians were injured in the missile strike, including young Nilay.80 Injuries were sustained from the force of the blast, shrapnel, and falling building debris. Several of the injured were children, including two-year-old Yagmur and four-year-old Bakhtiyar.81

The deadliest attack on Ganja took place less than a week later, in the early hours of 17 October 2020. At approximately 1am, there were reports of three loud explosions, as 9K72 Scud B Elbrus ballistic missiles hit Imamguliyeva Street and Khasiyev Street, both residential areas. Homes were reduced to rubble. In the aftermath of the attack rescue teams worked for hours searching through the debris, with sniffer dogs, periodically calling for silence to detect the sounds of any survivors.82 Two children who were initially reported as missing were subsequently found dead in the rubble.83 Three-year-old Khadija Shahnazarli was injured but survived. In hospital following the attack, she was initially unaware that her parents and baby sister had been killed.84

The attack claimed the lives of 16 civilians, including six children. 60 other civilians were injured.85 The destruction of civilian and public property was widespread.86 275 homes were damaged or destroyed. There was damage to a medical clinic, a school, a kindergarten, and to businesses.87

The 9BR team visited the area in November 2020 and witnessed the scale of the destruction. We spoke to survivors, including Ragibe Guliyeva, the grandmother of a 13-year-old Russian citizen named Artur Mayakov, who was killed in the attack.

Whilst the foundations of some homes were still visible, a large area was nothing but debris and rubble. It was not possible to ascertain where many of the homes had stood. Pieces of clothing, shoes, broken plates, twisted cutlery, children’s toys, and books were dispersed across the entire area. Houses that were still standing had sustained significant damage; many structures appeared dangerously unstable. Local residents, the adults and children who survived the attack, walked on the rubble of their former homes, some still searching for personal possessions.

ATTACKS ON BARDA

Barda city is located approximately 100km from the Armenian border and 30km from what was the ‘line of contact’.88 Between 27 September and 10 November 2020, attacks on Barda city and district resulted in the deaths of 29 civilians and the wounding of 104 civilians, as well as extensive damage to civilian property.89 Azerbaijan asserts that in its attacks on the district Armenian forces were deliberately targeting civilians and civilian objects, in violation of international humanitarian law.90

Attacks: 27 September – 10 November 2020

On 2 October 2020, Armenian forces subjected civilians in Azerbaijan to rocket and artillery fire. From their positions in the occupied areas of Azerbaijan, Armenian forces shelled the settlement of Amirli in the district of Barda.91 Barda was one of several Azerbaijani districts under fire and in the following days, more civilians were killed in missile strikes.92

On 5 October 2020, four Grad rockets were fired into the district, striking Hajibeyov Street and the intersection of Mammadguluzadeh Street and Aliyev Avenue.93 Shahriyar Mehdiyeva, a 59 year old woman, was killed in the strike, which also injured three others.94 The road connecting the cities of Barda and Tartar was hit by a Smerch missile on 8 October 2020.95 Further attacks were reported on 17 October 2020, when Barda was subjected to “intensive missile and artillery fire” along with several other districts in Azerbaijan, causing civilian casualties and the destruction of civilian and public property.96

On 27 October 2020, Barda was subjected to “intensive missile and heavy artillery fire” by Armenian forces. The village of Qarayusifli came under attack. Located 10km south of Barda city, Qarayusifli is a farming village and home to just over a thousand inhabitants. Five civilians, including a seven-year-old girl, were killed in an attack on the village.97

Local resident Rafig Isgandarov reported hearing “multiple, consecutive, explosions” as cluster bomblets rained down on a large area of village land. His seven-year-old granddaughter Aysu was killed by a fragment that landed in their neighbour’s livestock pen. The attack also killed Ekhtiram Khalil Ismayilov, 40, Ophelia Majid Jafarova, 50, and Almaz Salah Aliyeva, 56. Aybaniz Ashraf Akhmadova, 61, was killed while working in a field, her body “pierced with so many fragments that they had to wrap her […] in plastic to stop the bleeding.”98 Over a dozen civilians were injured.99

Child collects shrapnel ©Aygun RashidovaThe Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) carried out site visits in the aftermath of the attacks on 27 October 2020. ANAMA’s teams found remnants of one 300mm 9M525 rocket and 72 pieces of 9N235 bomblets.100 The attack on Qarayusifli was the subject of a formal complaint by Azerbaijan to the United Nations, where it was noted that this residential area was situated “far beyond the conflict zone.”101

The single most deadly strike on Azerbaijani civilians during the 44-day conflict took place the following day on 28 October 2020, when missiles loaded with cluster munitions hit busy commercial and residential areas in Barda city.

21 civilians were killed and over 90 others, including several children, were injured.102

The attack took place at approximately 1pm in a crowded area of the city. Three Smerch missiles – loaded with cluster bomblets – were fired on a busy intersection.103 One resident described how a bomb landed on Uzeyir Hajibeyov Street, a large avenue busy with commercial activity.104 In addition to multiple fatalities and injuries, there was serious damage and destruction to civilian property and infrastructure.105

The 9BR team visited the site of the 28 October 2020 attack in November 2020.106 It was clear that the area was civilian in nature, with a mix of commercial and residential properties. We went into local businesses, including a butcher shop where civilians had been killed. The impact damage from the weapons deployed was still visible on the street intersection, as was the widespread damage to homes and small businesses. We observed destruction which was consistent with cluster bomblets and fragments, dispersed over a large area. It should be noted that the attack took place in close proximity to Barda Central Hospital.107

On 7 November 2020, Shahmali Rahimov was killed when Armenian forces shelled the village of Yeni Ayrica. He was 16 years old.108

Civilian infrastructure

The attacks on Barda city resulted in widespread damage and destruction of civilian property and infrastructure. This included but was not limited to destruction and damage to private homes and apartment buildings, office buildings, commercial businesses, schools, hospitals, clinics, vehicles and roads. The 9BR team observed damage to commercial properties in Barda city, where the most significant destruction took place during the attack on 28 October 2020.109

The Office of the Prosecutor General of Azerbaijan reported that between 27 September – 10 November 2020, 156 civilian properties sustained severe damage. This figure includes 46 homes, 62 vehicles, and 48 businesses (including shops, beauty salons, a bakery, a pharmacy, a car wash, and a garage). It was reported that there was damage to the Barda Medical and Diagnostic Centre, a building of the Fire Protection Department, and a passport registration office.110 As a result of the bombardment on 28 October 2020, both buildings of the Olympic Sport Complex (with 3.8 hectares) were reportedly damaged beyond use.111

Attacks on Terter

During the recent conflict, the Azerbaijani district of Terter was subjected to near daily shelling and attack. In contrast to the incidents in Barda and Ganja considered in this Interim Report, no single strike resulted in a large number of civilian casualties. However, civilian fatalities and/or injuries occurred on a daily basis from the outset of renewed hostilities on 27 September 2020. Villages and settlements across this largely rural district sustained extensive damage. During the six-week conflict, 17 civilians in the district were killed and 58 others were wounded.112

Terter district was partitioned and partly occupied by Armenian forces after the first Nagorno-Karabakh war. Accordingly, the part of the district remaining under Azerbaijani overall control was located on the ‘line of contact’. The district is made up of many rural villages and settlements, its capital city Terter and the town of Aqhdara. The latest census records a population for the district of just over 104,000.113

Attacks: 27 September – 10 November 2020

Villages in the district bore the brunt of daily attacks. Armenian forces attacked Terter district in the first hours of the renewed conflict on 27 September 2020, when the village of Qapanli was shelled using “large-calibre weapons, mortar launchers and artillery.”114 Two schools – one in the Shikharkh settlement and one in Terter city – were damaged by artillery and mortar fire.115

Five civilians were killed and several injured in attacks on 28 and 29 September 2020.116 Civilians injured in the initial days of the conflict include 80-year-old Asif Mustafayev, whose home in Gazyan village was completely destroyed in an attack on 29 September 2020.117 38-year-old Zabil Hasanov was killed by shrapnel at the bus station in Terter city on the morning of 1 October 2020; the bus station was also badly damaged.118 It was reported that on 2 October 2020 alone, over 2,000 shells hit the district, resulting in widespread damage to communities, including settlements for the internally displaced.119

The shelling of villages and settlements in the district continued throughout October 2020, resulting in further destruction to civilian property and infrastructure, injury, and death.

The district was attacked on 11 October 2020 in the hours following the establishment of a humanitarian ceasefire on 10 October 2020, and again in the following two days.120 On 14 October 2020, a shell landed in the yard of a secondary school; several villagers were hospitalised as a result.121

One of the deadliest incidents took place on 15 October 2020 at approximately 1pm, when an attack struck a funeral procession at Terter City Cemetery, killing four civilians: Parviz Orujov, Vasif Rustamov, Shakir Zamanov and Isgandar Amirov.122 Four others – Fuzuli Mammadov, Elsever Allahverdiyev, Nofel Amirov and Rafael Gazanfarli – were hospitalised with serious injuries.123 Fuzuli Mammadov, one of the injured, told Human Rights Watch that the funeral ceremony was held to bury his aunt. He recounted that the group was carrying his aunt’s body when they heard “whistling’’ overhead, and a munition exploded just 50 metres away, followed shortly by another which hit a grave.124 Several tombs and a civilian vehicle were destroyed in the attack.125

On 19 October 2020, the district was again under “intensive rocket artillery fire”. Salimov Niyaz, a 58-year-old resident of Alasgarli village, was injured and hospitalised when a shell hit the yard outside his home.126 Two residents of the Jamilly village – Anar Rasul (26 years) and Guliyev Anar (36 years) – were killed the following day on 20 October 2020; Shabanov Rasul (48 years) was wounded and his home seriously damaged.127 16-year-old Orxan Ismayilzade was killed in further bombardment of Terter city on 24 October 2020.128

In late October 2020, Azerbaijan submitted a formal letter to the UN Secretary General, reporting that Terter district and city had been under “heavy artillery shelling” since 27 September 2020.129 On 27 October 2020, during shelling of Terter city and villages, journalists from Euronews and their vehicle were reportedly hit by a Kornet anti-tank missile whilst in the Talish and Sugovushan villages.130 Further attacks continued in early November,131 with Terter district officials reporting that 52 missiles struck the villages of Shikharkh, Gazyan, Saklabad and Gapanly.132

There was extensive damage and destruction to civilian property and infrastructure.133 It was reported that by 13 October 2020, 12 schools in the district had been destroyed or sustained damage.134 Between 27 September and 02 November 2020, 135 houses had been destroyed and 915 had been damaged.135

Shikharkh: Settlement for the Internally Displaced

Shikharkh is a civilian settlement located on the western edge of Terter city, and is almost fully surrounded by agricultural fields. The settlement was established in 2017 to accommodate some of the thousands of internally displaced from the first Nagorno-Karabakh war.136

Azerbaijan has one of the highest rates of displaced persons per capita in the world.137 Between 1988-1994, 600,000 Azerbaijanis were displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh and its surrounding areas, with a further 150,000 refugees from Armenia.138

Shikharkh is a modern development made up of 34 apartment buildings and houses approximately 1,170 families – with approximately 4,800 residents.139 Within the development there are a number of schools (including a music school) and facilities such as a playground and a sportsground. The residents now settled in Shikharkh were displaced from various regions during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war, but are predominantly from the Kelbajar area.

During the 44-day conflict, families in Shikharkh were subjected to near daily shelling from Armenian positions. Many of the residents, already the victims of displacement during war, fled Shikharkh in the hopes of finding safety. Those who remained sheltered in basements.140

Most of the 34 apartment buildings sustained damage from the shelling attacks, with some flats being damaged beyond use.141 In addition to damage to homes, there was extensive damage to the schools and educational centres in the settlement.142

During the 9BR team’s visit to Shikharkh settlement in November 2020, we witnessed the extensive damage caused to civilian homes, schools, and other facilities, such as the music school.

The Village Folklore House is a large community centre within Shikharkh which hosted cultural activities and events. In 2019, the centre held an event for the IDPs of Shikharkh, organised by the United Nations and the State Committee for Affairs of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons.143 The Village Folklore House is now in ruins, having sustained a direct missile hit. The missile came through the roof, destroying the structure and leaving a large crater in what was the main floor.

The surface of almost every apartment building in Shikharkh was pockmarked from shelling, and most windows were shattered, leaving dangerous shards on damaged frames. Glass and shrapnel were strewn in the grass and streets, and across playgrounds. Many residents are living in badly damaged flats, now precarious structures following repeated shelling. Those living in damaged apartments – with shattered windows and partially destroyed walls – faced a winter being exposed to the elements.

Between 27 September 2020 and 10 November 2020, attacks by Armenian forces on cities, villages and settlements in Azerbaijan resulted in the death and wounding of civilians, as well as extensive damage to civilian property and infrastructure.144

Attacks by Armenian forces killed 100 Azerbaijani civilians and injured 416 others.145 As detailed in official crime reports, civilian casualties occurred on a near daily basis from the outbreak of hostilities on 27 September 2020 until the signing of the ceasefire agreement on 10 November 2020. Almost half of the civilian fatalities occurred in ‘single-fatality’ incidents. Further, we note that during this period there were also dozens of attacks on villages, settlements and cities which did not result in civilian fatalities, but left civilians wounded, and civilian property and infrastructure destroyed or damaged.146

In mid-November 2020, the 9BR team carried out visits to incident locations in the Azerbaijani districts of Barda, Terter, Ganja and Goranboy. We witnessed the aftermath of missile strikes in civilian areas and saw the scale and nature of destruction to civilian property. We spoke to survivors and family members of those killed in the attacks. Our observations in situ were supplemented by meetings with representatives of official bodies, non-governmental organisations and specialist agencies. We reviewed criminal case files and reports which included the types of weaponry recovered and the nature of the destruction, deaths and injuries.

This section considers in detail five attacks (‘key incidents’) by Armenian forces which all resulted in multiple civilian casualties.147 For the purposes of this report, it was not possible to verify the factual circumstances or consider the lawfulness of all attacks leading to the deaths and injuries to civilians, or destruction of civilian property and infrastructure. Further, this report does not consider the conduct of hostilities between Azerbaijani and Armenian armed forces.

Based on these observations and reports, there are grounds to the allegation that crimes under international law were committed by Armenian forces during the recent conflict (27 September 2020 – 10 November 2020). Armenian forces carried out seemingly indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks on cities and villages in Azerbaijan, where there were no military targets apparently present. These attacks resulted in civilian fatalities and injuries, and widespread destruction and damage to civilian property and infrastructure.

Further investigation would contribute to ascertaining whether some of these key incidents may have been part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against the civilian population of Azerbaijan. The number and nature of these indiscriminate attacks may indicate that Armenian forces pursued a deliberate policy of targeting Azerbaijan civilians.

Key incidents

This section considers five key incidents. These are:

27 September 2020: Gashalti village, Goranboy district. Five members of the Gurbanov family, including two children, were killed in an artillery attack on their home.

11 October 2020: Ganja city. 10 civilians were killed and 39 civilians were injured in a Scud-b missile strike attack on a residential area of the city.

17 October 2020: Ganja city. 15 civilians, including six children, were killed and 60 civilians were injured in a Scud-b missile strike on a residential area of the city.

27 October 2020: Garayusifli village, Barda district. Five civilians were killed and 12 civilians injured in a cluster munitions attack on this farming village.

28 October 2020: Barda city. 21 civilians were killed and over 90 were injured in a cluster munitions attack on a busy commercial and residential area of the city.

In total, 56 civilians were killed and over 200 civilians were injured in these five attacks. These attacks also resulted in extensive damage to civilian property and infrastructure.148

Grave breach of intentionally directing attacks against civilians not taking direct part in hostilities

We recall that the civilian population and individual civilians are protected against direct attacks. Making the civilian population or individual civilians the object of attack is a grave breach of Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions.149

Indiscriminate attacks are prohibited as they are of a nature to strike military objectives or civilians (and civilian objects) without distinction.

Indiscriminate attacks may qualify as an attack directed against civilians or give rise to the inference that an attack was directed against civilians.150 A direct attack on civilians can be inferred from the indiscriminate character of the weapon used.151

Civilians and the Civilian Population

The key incidents considered in this report occurred in districts of Azerbaijan which are adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh, and other Azerbaijani territory then under occupation by Armenia. However, these strikes occurred in villages and cities a considerable distance from the area of active hostilities between Azerbaijani and Armenian armed forces. For instance, Ganja city and Barda city are respectively 97km and 30km from what was the ‘line of contact’.

There should be no dispute that the five attacks took place in civilian locations, be they urban or village settings. Armenian forces launched a Grad artillery salvo on a village home in Gashalti on 27 September 2020. Scud-b missiles struck residential areas of Ganja city on 11 October and 17 October 2020. Cluster munitions bomblets hit the village of Garayusifli on 27 October and a busy commercial and residential area of Barda city the following day on 28 October 2020. Civilian ‘objects’ – mostly homes, but also businesses, schools, and clinics – were destroyed or damaged in the attacks.

There is no suggestion that any civilians were participating – directly or indirectly – in hostilities or otherwise engaged with Azerbaijan’s military activities in these locations.

Grad missile in Gashalti Village

On the first day of renewed hostilities on 27 September 2020, Armenian forces fired artillery at a home in the village of Gashalti in Goranboy district, killing five members of the Gurbanov family, including two children.

ANAMA reports that the weapon was a Grad 9M22u, which is large calibre artillery.152 The Martić Trial Chamber relied on expert evidence to find that the choice of Orkan rockets would “not have been appropriate had the purpose been to damage military targets,”153 and concluded that “in respect of its accuracy and striking force, the use of the Orkan rocket in this case was not designed to hit military target but to terrorise the civilians of Zagreb.”154

Although not covered by a specific ban, whether conventional or customary, it may be suggested that a Grad 9M22u should not be fired into civilian areas as it cannot distinguish between military targets, civilians, and civilian objects.155

Elbrus/Scud-B ballistic missiles in Ganja

Armenian forces attacked residential areas of Ganja city on 11 October and 17 October 2020 with Elbrus/Scud-B ballistic missiles.156 The missile strike on 11 October 2020 killed 10 civilians. The strike on 17 October 2020 killed 15 civilians, including six children. A further 99 other civilians were injured in these two attacks.157 The attacks resulted in widespread destruction and damage to civilian property far outside the impact location. Following the first attack, rescue workers reportedly found body parts more than 100 metres from where the missile struck.158

The Azerbaijan National Agency for Mine Action (ANAMA) reports that Armenian forces fired a total of 13 Elbrus/Scud-B ballistic missiles on Azerbaijan during the recent conflict.159

Scud-B are long range missiles and can be fired from a distance of 300km away.160 They are highly destructive weapons and carry a payload of 985kg. They are indiscriminate weapons when used in this context as they cannot by their design be directed at a specific military objective, and so cannot distinguish between military targets and civilians and civilian property.161

Cluster munitions in Barda

Armenian forces attacked the farming village of Garayusifli in Barda district on 27 October 2020 and Barda city on 28 October 2020. Cluster munitions were used in both attacks. One 9M525 Smerch rocket was fired into the farming village of Garayusifli, killing five civilians. Three Smerch missiles (two 9M525, one 9M528) were fired into Barda city the following day, killing 21 civilians. A total of 94 other civilians were injured in these two attacks.

The Russian ‘Smerch’ (‘Tornado’) Multiple Launch Rocket System carries twelve rockets, with each carrying a standard warhead of seventy-two submunitions. A salvo of twelve rockets covers 672,000 square meters.163

Rockets containing cluster munitions can be dropped by aircraft or, as in the case of the Smerch system, be fired from the ground by rocket launchers. The rockets typically open in the air and disperse cluster bomblets over a wide area; the tail of the rocket will continue along its trajectory and then hit the ground.164

When fired into civilian population centres, it may be suggested that cluster munitions are indiscriminate weapons. Their wide zone of submunition dispersal places anyone, be they civilians or combatants, and anything, be it civilian or military property, in the attack zone and at risk of death, injury, or damage. Further, cluster bomblets which do not explode on impact can remain armed, placing civilians at risk over the longer term.165

Precautions

International humanitarian law requires those launching attacks to take precautions to spare the civilian population, civilians and civilian objects.166 Precautions include effective advance warning of attacks which may affect the civilian population, unless circumstances do not permit.167 We have not seen evidence of any effective warnings being communicated by Armenian forces to the Azerbaijani civilian population in advance of any attack during the recent conflict.168

On 4 October 2020, Arayik Harutyunyan, the ‘president’ of the de facto authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, posted tweets (in English) calling on the Azerbaijani population to “leave area in advance” of a bombardment of Ganja. Similarly, Vahram Poghosyan, spokesperson for the self-proclaimed authorities in Nagorno-Karabakh, told an Armenian news agency in early October 2020 that their forces were “not targeting the civilian population but military facilities permanently deployed in large cities” saying that civilians should leave their homes to escape harm.

These are not effective warnings; both were unspecified in terms of date and time and refer to leaving an unspecified area within a city (Ganja) or generally to leave “large cities”. The fact of the warnings is evidence that the forces were aware of the risk to the civilian population caused by the attacks. Further, these purported warnings were communicated in English and Armenian – not Azerbaijani – on a social media platform or Armenian television channel.

Conclusions: targeting civilians